Dynamic Compilers part 2

C++ method call

each object has a pointer to a vtable, which is a table of function pointers to all the virtual functions

each derived object has its own vtable, which has the same offsets for all the common virtual functions

to find the code takes two dereferences

- find the vtable (one per class) (one load)

- at a fixed offset (determined by the virtual function name) find the code (second load)

a python example

more flexible

- find the hash table (one per instance)

- lookup the virtual function in the hash table

class Thing:

def __init__(self, kind):

self.kind = kind

thing = Thing('car')

def honk(self):

print(f"{self.kind} says Honk")

thing.honk = honk.__get__(thing) ## add a method dynamically to one instance

thing.honk() ## call it

honk.__get__(thing) returns a bound method, when this method is called thing is passed as first argument

dynamic chunks

So far:

- run interpreter or tier 0 compiler

- collect statistics on call counts or branch counts

- when count is high enough recompile the hot functions

- specialize the hot functions based on common values

The unit of compilation is the static function

an alterative is called trace compilation

- run interpreter or tier 0 compiler

- collect the statements executed (no not collect control flow)

- this produces a linear trace of instructions

- recompile the trace using optimizations like value numbering

- if the next time the code executes, it takes a different path, fix things up

trace compilation 0

In a linear trace the number of assumptions you’re making accumulates as you execute [towards the end of the trace you have the most assumptions built up]

If you have an always-taken control flow, e.g. some virtual function call that’s always calling the same actual function, a tracing compiler will treat all back-to-back branches as one set of straight line code

execute this all back to back, and, whenever convenient, check whether any of those assumptions were wrong”

cold path

On the “cold path” – again, when it’s convenient undo all the inapplicable things if it turns out the branches weren’t true

Called a “bailout” [“bailing out” of the trace]

At a bailout there is new information. something you didn’t observe when you were tracing

You trust that everything you’ve trace is going to happen, it’s all going to well, and you’re going to be able to optimize for it

But then at runtime, when convenient, you’re going to check, and then bail if you were wrong, and have the rollback on the cold path

So the hot path, the one you’re pretty sure is going to execute, is quite optimal

trace compilation 2

tracing jit: extract a hot path (not a function)

Hot paths are compiled as a single basic block, but the path might go through a call

gamble: next execution starting at this point, go the same way, no branches leave the path

generate machine code for hot paths interpret the rest of the program

unlike specialization, tracing assumes the same path but not the same values

an example (x = 42)

function main(x){

y = x +1

if x <100 {

z = f(y)

} else {

z = g(y)

}

return z

}

function f(a){

return a -1

}

- y = x +1

- guard(x < 100)

- a = y

- z = a - 1

- return z

guards at divergence, guards never return

optimize assuming guards are true, ok to be slow if guard is false

move guards up

why is this a good idea?

. . .

- fail fast

- longer region to optimize

use local value numbering

- guard(x < 100)

- y = x + 1

- a = y

- z = a - 1

- return z

how do this in Bril?

3 new operations (sort of like out-of-order instructions)

- speculate - Enter a speculative execution context. No arguments.

- commit - End the current speculative context, committing the current speculative state as the “real” state. No arguments.

- guard - Check a condition and possibly abort the current speculative context. One argument, the Boolean condition, and one label, to which control is transferred on abort.

example

b: bool = const false;

v: int = const 4; v == 4

speculate; v: int = const 2; v == 2 (speculate state) guard b .failed; v == 2 (speculate state) commit;

.failed: print v; v == 4

implementation

you can add a tracer to an interpreter

In a lot of language environments you’ll have an interpreter that’s executing “op at a time”

hook in a tracer which observes what the interpreter is doing and “make some machine code on the side” based on how the interpreter ran

you can implement just a subset of the operations [ed: you might call this property “compiler completeness” for your op set

common bytecode operations

implement only the common ones and simply end the trace when you hit one that was not implemented, because it was uncommon

You can build up this trace JIT-ing capability over time, because the system is built with this assumption you can bail out of the trace for whatever reason and go back to thr interpreter

an example

Could imagine making a JIT that just: Covered MULs and ADDs and could make fused/composite MUL/ADD bytecode combinations

Specialize that for one common type; e.g. if you have many types in your language, could support that just for integer types, or just for FP ops e.g. if it were numerical code, and then just bail if any other types showed up at runtime;

trace invariants: suppose traces call to other traces;

trace1 set of ops A, trace2 with set of ops B and we see a transfer from A to B

make sure that the assumptions between those two things are lining up – called trace fusion

know the invariants (i.e. “what must be true”) on the exit from A and the entry to B are lining up / compatible with each other

method inlining

In trace compiler you just execute through methods

Inlining kind of the natural path of compilation when doing trace compilation – just linear execution where the jumps/calls/returns simply disappear

tail duplication

it is common that multiple traces have a common tail

for() {

if op_Eq{

op1

} else {

op2

}

}

op_t

op_a

op_i

op_l

trace0: op_eq quard\true op1 op_t op_a op_i op_l

trace1: \false op2 op_t op_a op_i op_l

two traces with the same ending, could generate

one copy of the tail- with arguments showing the header

two copies of the tail- frozen header

adding traces to bril

How to modify the reference interpreter (warning typescript!)

brili

there are two functions to consider

- evalFunc interprets a function by calling evalInstr on each instruction

- evalInstr interprets one instruction, large case statement for each instruction

print instructions as they execute

- figure out when to start and when to stop

- how to print instructions (modify evalInstr by printing instructions) console.log(instr)

you have to optimize the trace and put it back

traces and users

when a trace works well- it looks amazing - it finds the inner loop and optimizes even through libraries

but users find in hard to understand what the compiler did,

a tiny source change can make a big trace change

hard to fit in a debugger

security is a problem

pytorch 2.0

ml frameworks have two modes

Eager Mode

- Preferred by users

- Easier to use programming model

- Easy to debug

a + b + c executes two calls to torch.add (if they are tensors)

no place to optimize, allows any kind of python, and any control flow

- PyTorch is a primarily an eager mode framework

Graph Mode

- Preferred by backends and framework builders

- Easier to optimize with a compiler

- Easier to do automated transformations

construct a graph with two add nodes and 3 input nodes, then execute the graph

easy to optimize, only graph nodes allowed, no control flow

Main optimization is fusing operations to avoid memory copies

how does the compiler fit

in Eager mode there is only a library - no compiler

if you have a matmul followed by an activation function, it is up to the developer to notice that the memory traffic is more expensive then the activation and its up to the developer to know there is another pytorch call (2000 different calls) which does the combined operation and it is up to the developer to change the code

if graph mode (compiler writers call this defered or late) the operations get recorded (not executed) and only get executed when we need the result

PyTorch’s Many Attempts at Graph Modes

torch.jit.trace

- Record + replay

- Unsound

- Can give incorrect results because it ignores Python part of program

torch. jit.script

- AOT parses Python into graph format

- Only works on ~45% of real world models

- High effort to “TorchScript” models

- PyTorch Models Are Not Static Graphs

PyTorch users write models where program graphs are impossible

Convert tensors to native Python types (x.item(), x.tolist(), int(x), etc)

Use other frameworks (numpy/xarray/etc) for part of their model

Data dependent Python control flow or other dynamism Exceptions, closures, generators, classes, etc

torch xla

defered execution. rather then do the graph operation, just save it and execute as late as possible

very slow, big performance cliffs

torch.compile(model) - converts a pytorch eager program to a graph

torch.dynamo - which dynamically captures Python code execution and creates a static computational graph.

torch.Inductor- compiler that optimimzes static computation graphs

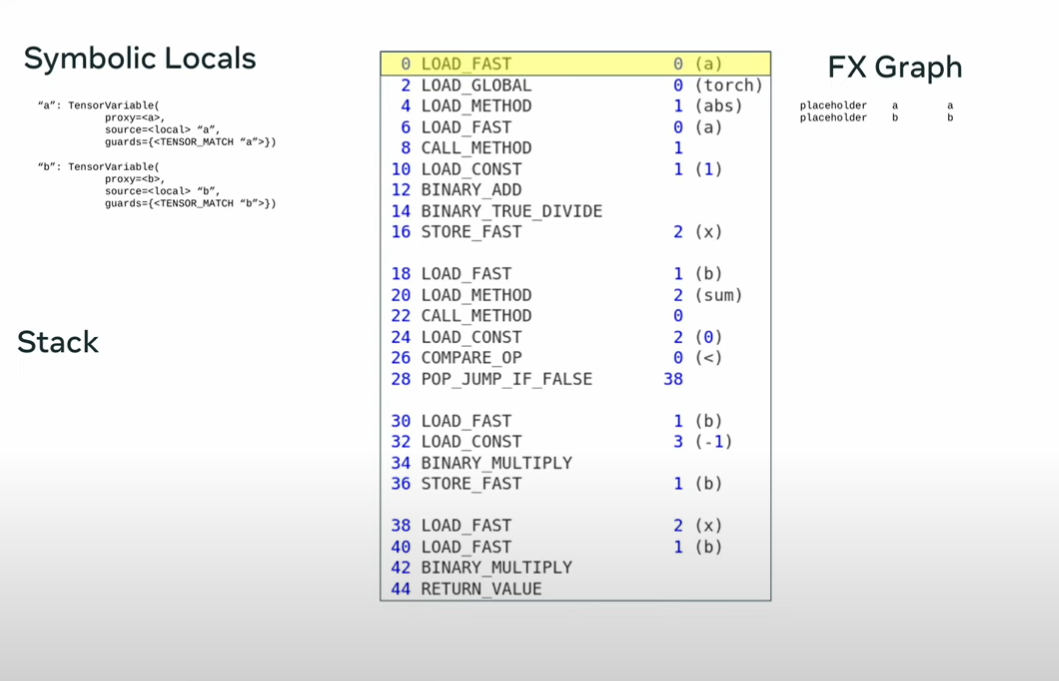

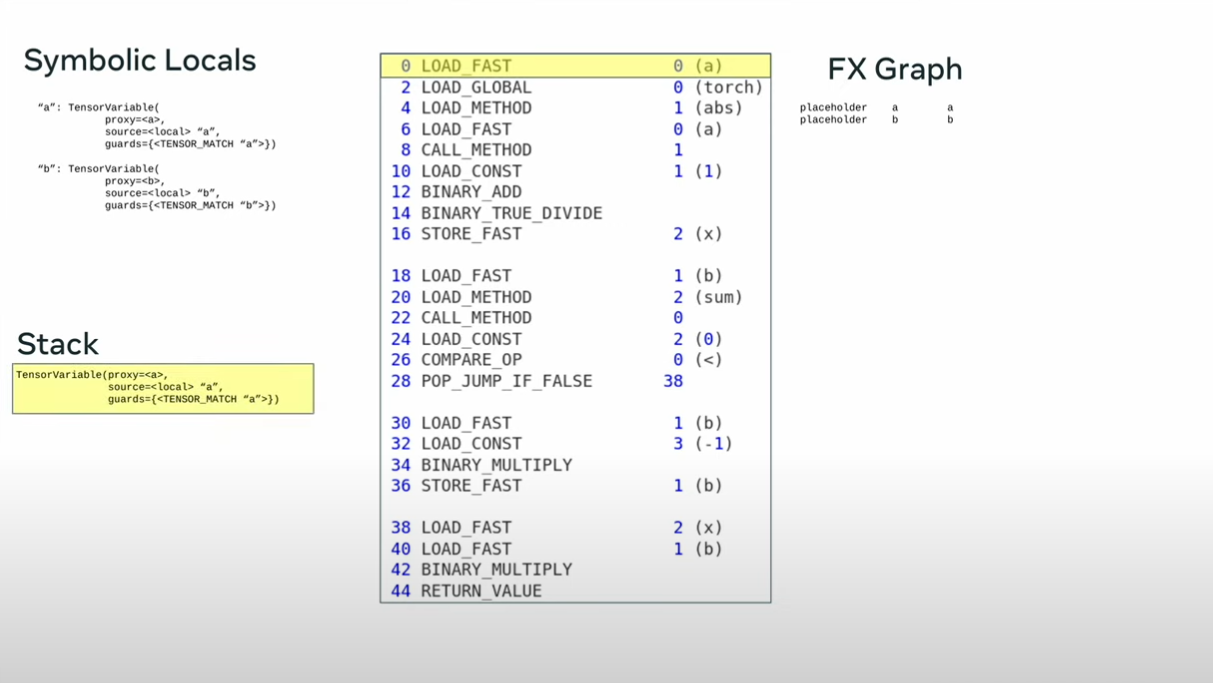

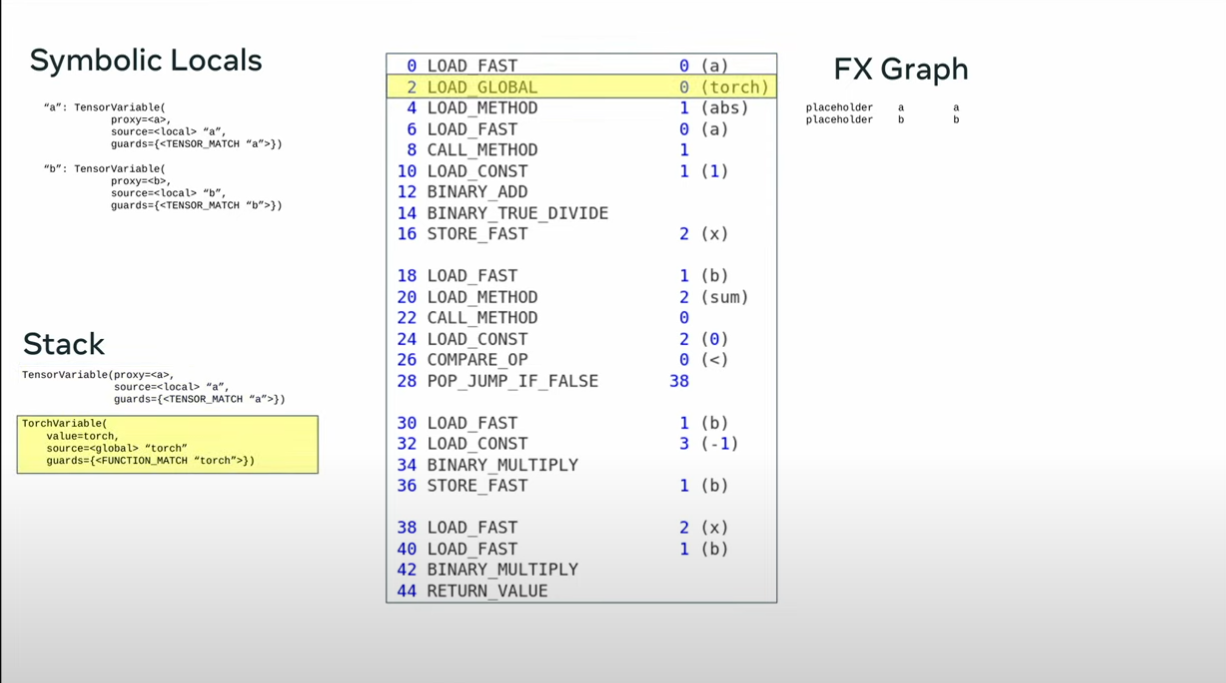

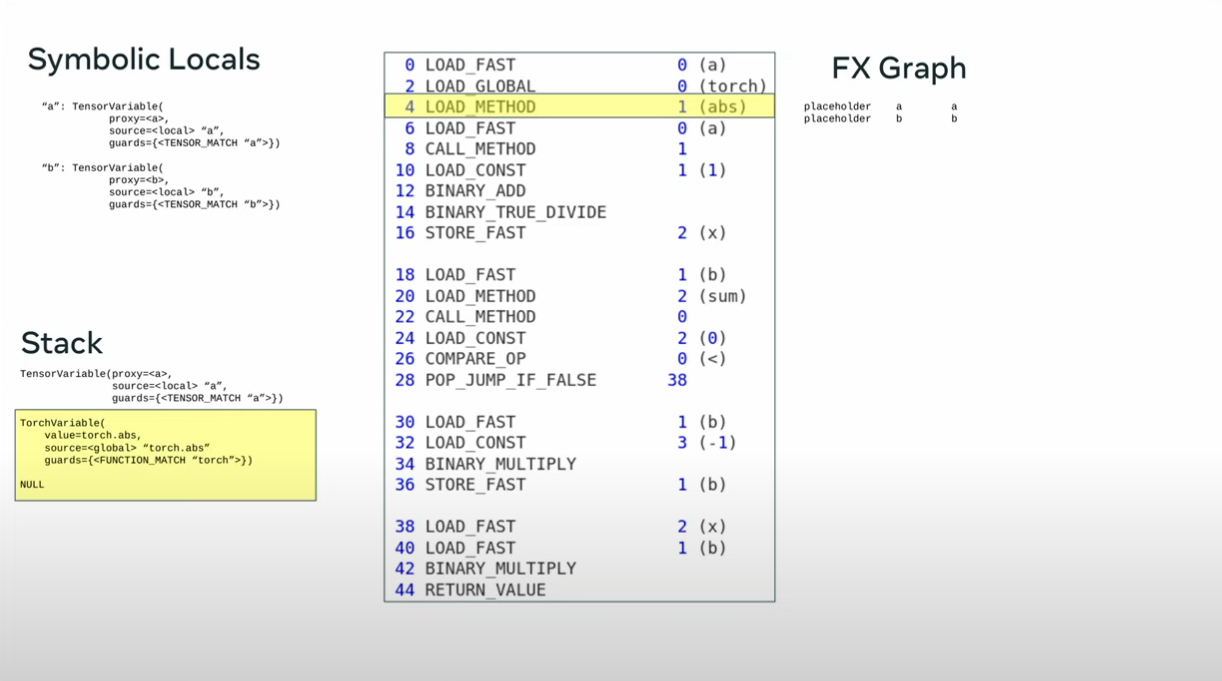

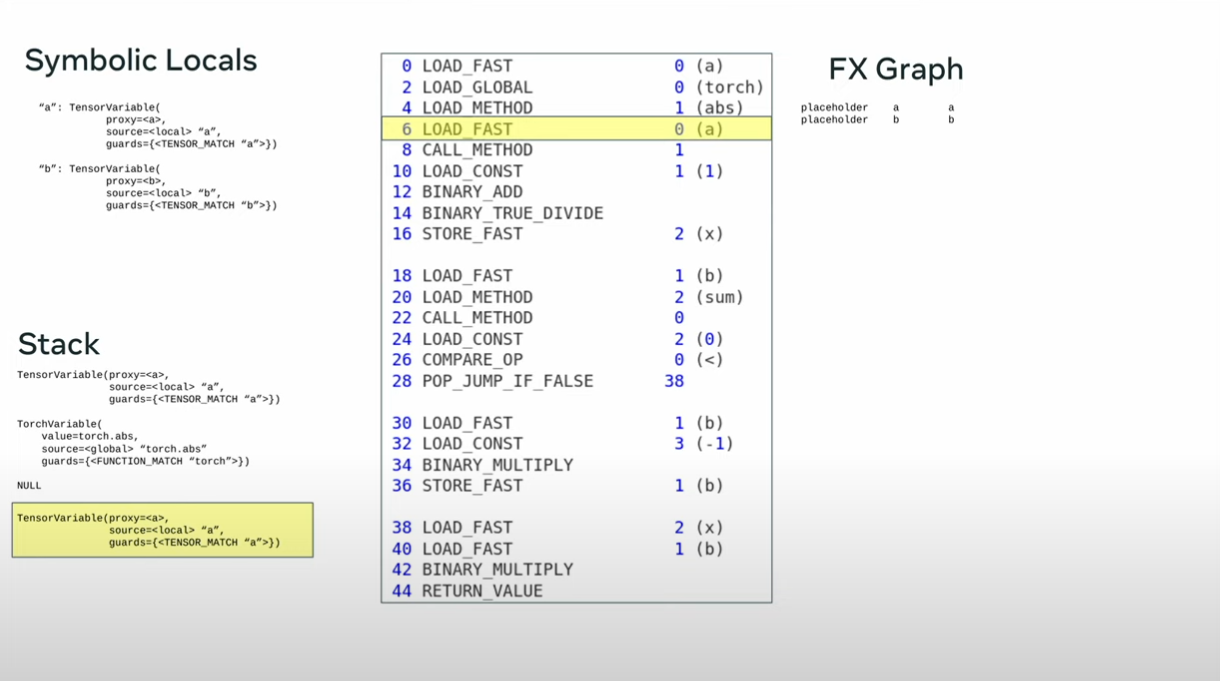

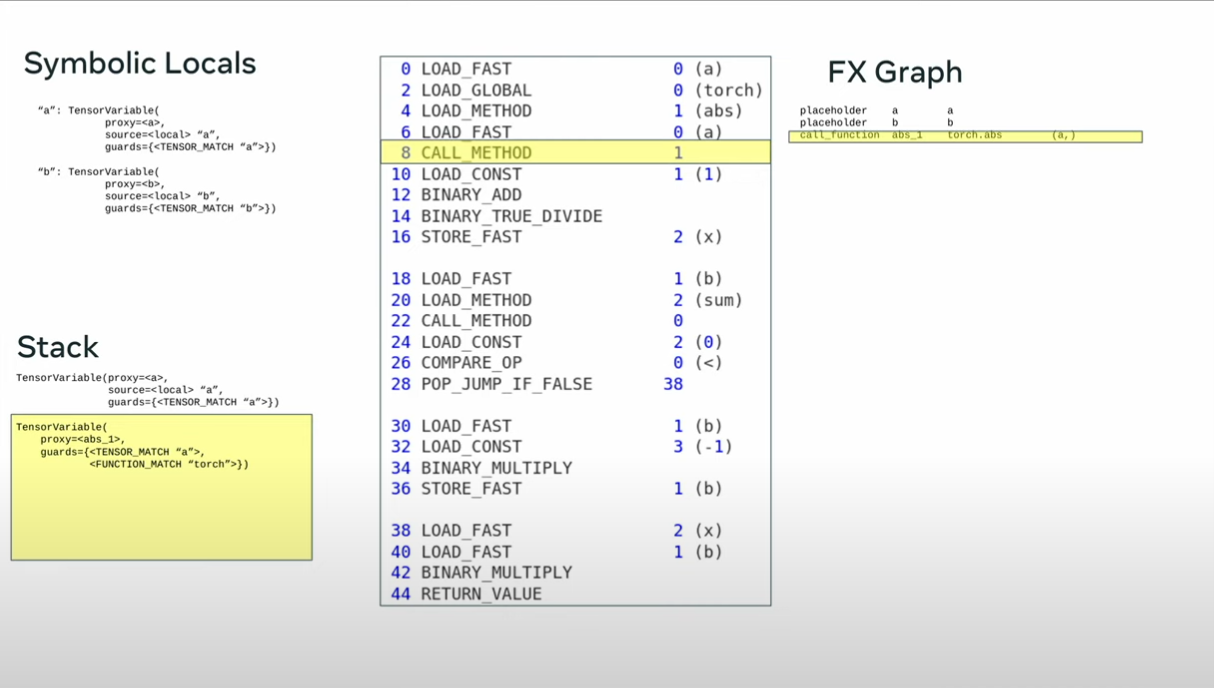

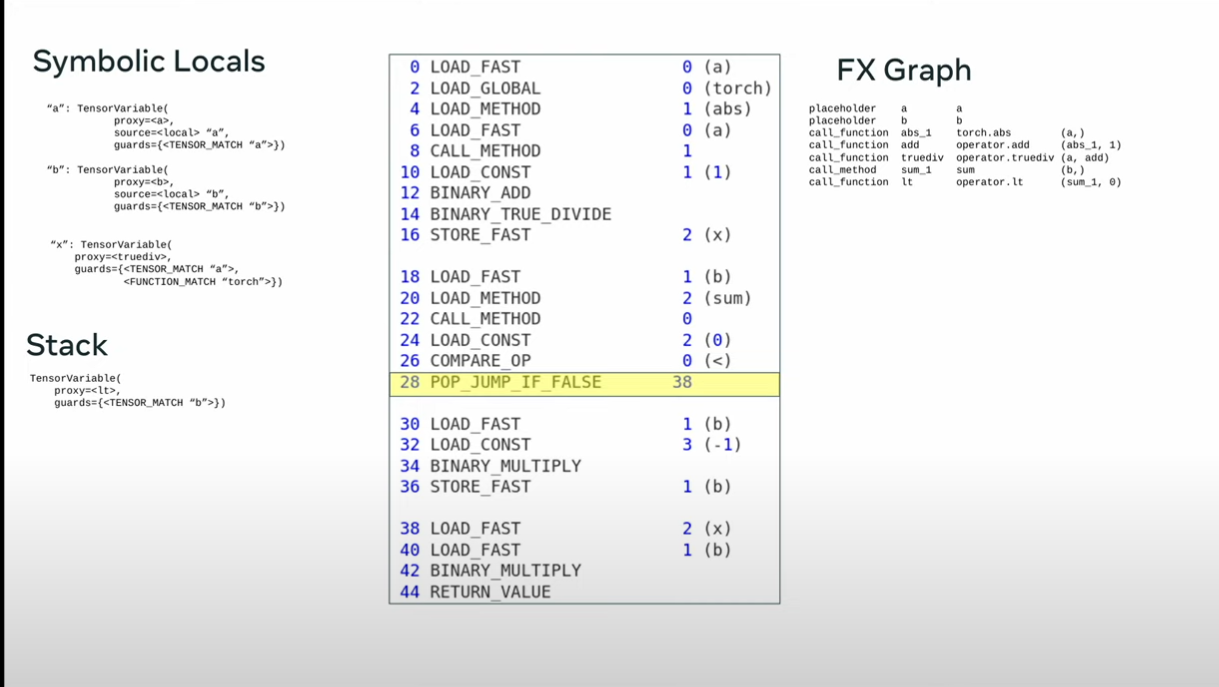

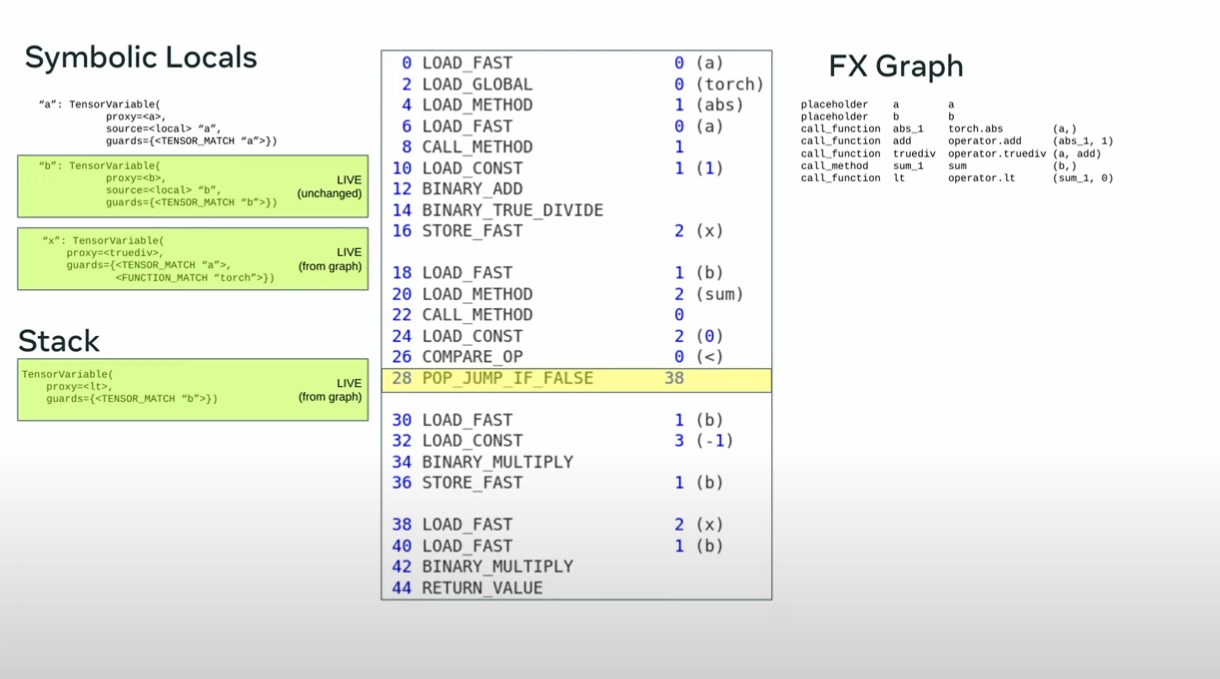

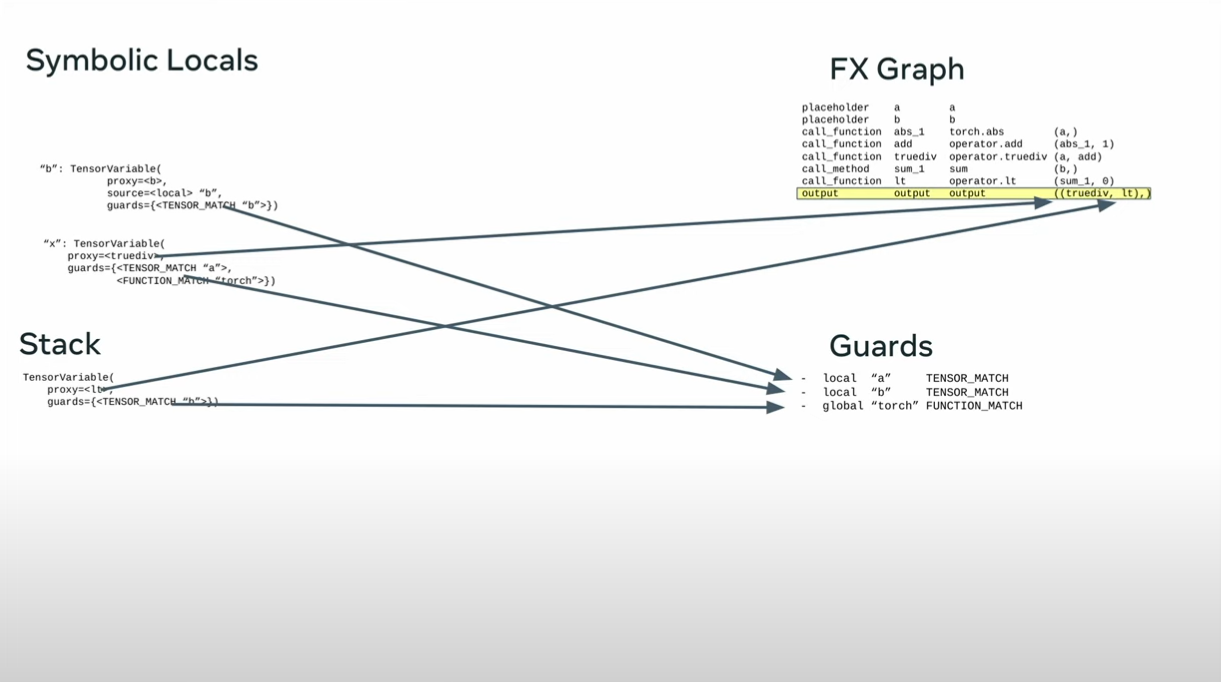

dynamo

import torch

from typing import List

import torch._dynamo

torch._dynamo.config.suppress_errors = True

def my_compiler(gm: torch.fx.GraphModule, example_inputs: List[torch.Tensor]):

print("my compiler() called with fx graph")

gm.graph.print_tabular()

return gm

@torch.compile(backend=my_compiler)

def toy_example(a,b):

x = a / (torch.abs(a)+1)

if b.sum() < 0:

b = b * -1

return x *b

for _ in range(100):

toy_example(torch.randn(10), torch.randn(10))

output

def toy_example(a,b):

x = a / (torch.abs(a)+1)

if b.sum() < 0:

b = b * -1

return x *b

opcode name target args

------ ------ --------- -----------

placeholder l_a_ L_a_ ()

placeholder l_b_ L_b_ ()

call_function abs_1 <abs> (l_a_,)

call_function add <add> (abs_1, 1)

call_function x <truediv> (l_a_, add)

call_method sum_1 sum (l_b_,)

call_function lt <lt> (sum_1, 0)

output output output ((x, lt),)

------ ------ --------- -----------

placeholder l_b_ L_b_ ()

placeholder l_x_ L_x_ ()

call_function b <mul> (l_b_, -1)

call_function mul_1 <mul> (l_x_, b)

output output output ((mul_1,),)

------ ------ --------- -----------

placeholder l_x_ L_x_ ()

placeholder l_b_ L_b_ ()

call_function mul <mul> (l_x_, l_b_)

output output output ((mul,),)

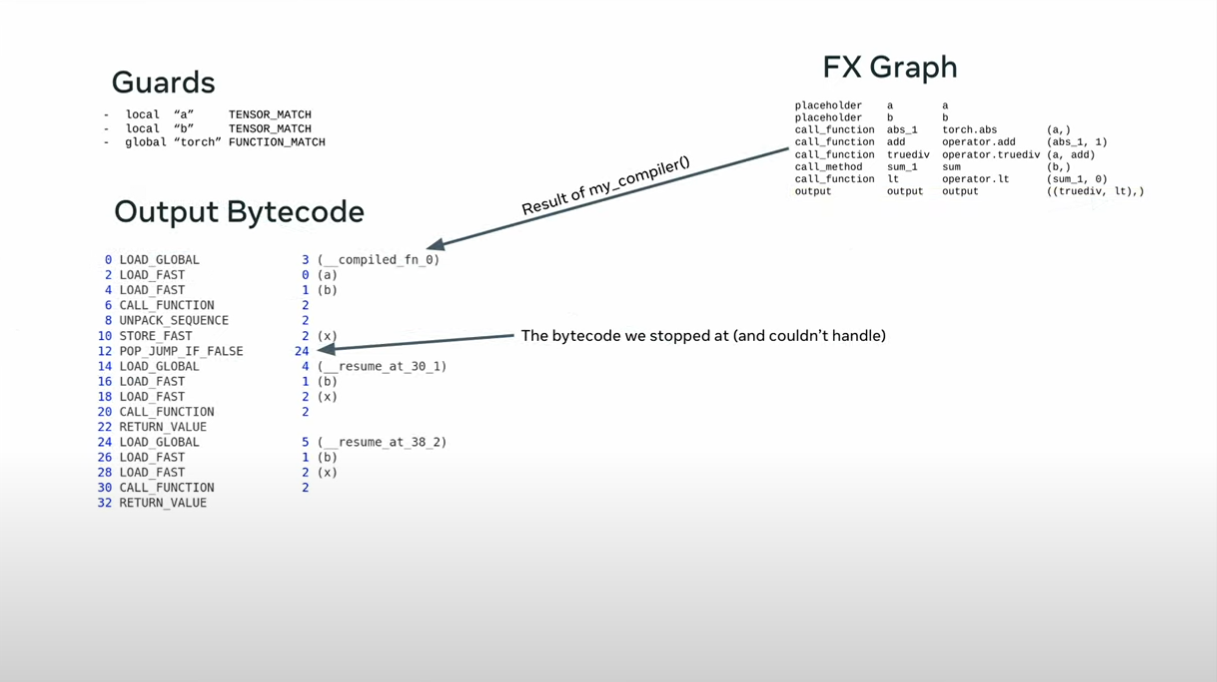

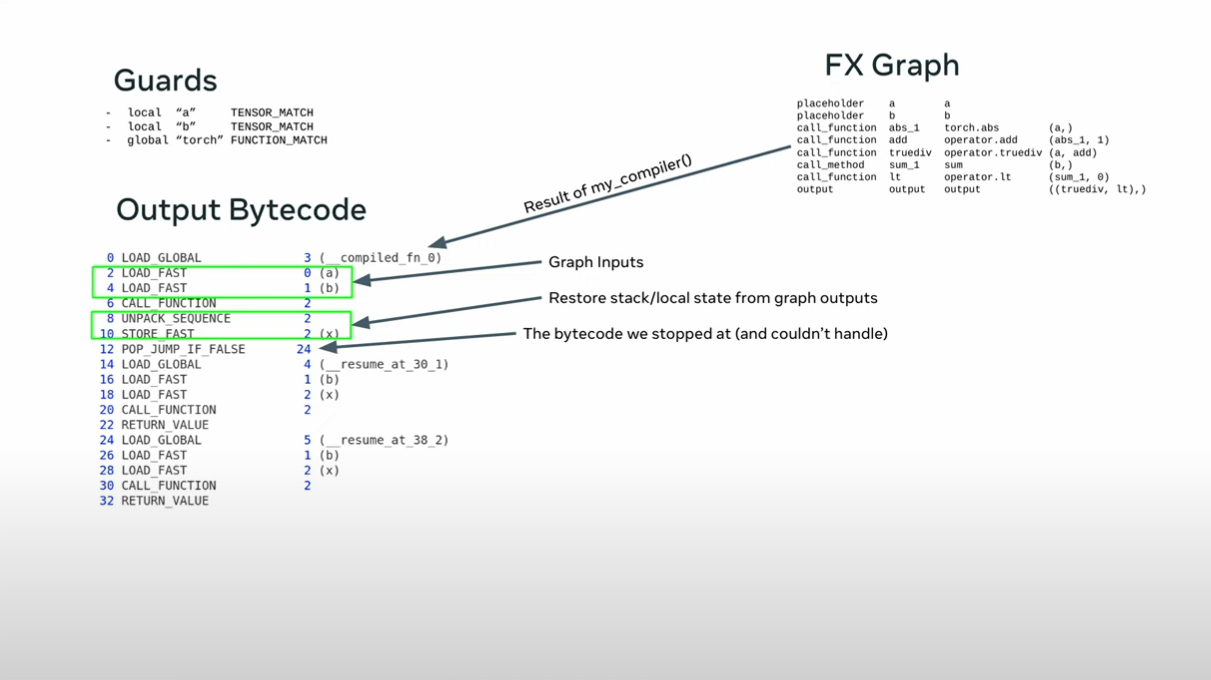

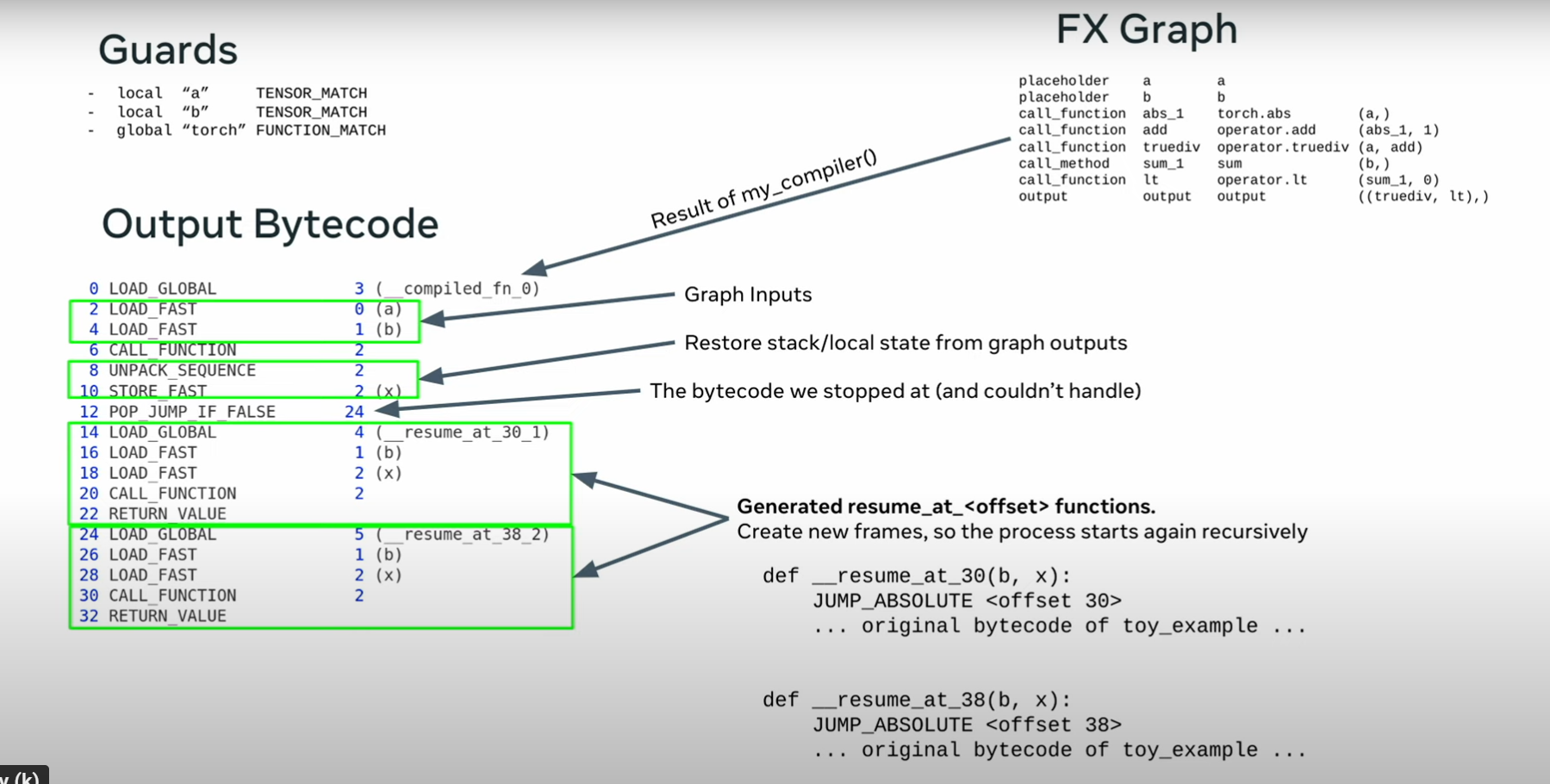

implementation

python builds a frameObject (pointer to codeObject + arguments)

passes this to eval

codeObject allows for extra user data and for a user function to be called between the frameObject and eval

This makes it easy to add a custom JIT

split the function into two parts - the python part and the torch part

This is reused if the guards pass

pytorch example 1

def toy_example(a,b):

x = a / (torch.abs(a)+1)

if b.sum() < 0:

b = b * -1

return x *b

for _ in range(100):

toy_example(torch.randn(10), torch.randn(10))

sometimes the sum is negative but not always

graph

| placeholder |

l_a_ |

L_a_ |

() |

| placeholder |

l_b_ |

L_b_ |

() |

| call_function |

abs_1 |

<built-in method abs of type object at 0x728736add8a0> |

(l_a_,) |

| call_function |

add |

|

(abs_1, 1) |

| call_function |

x |

|

(l_a_, add) |

| call_method |

sum_1 |

sum |

(l_b_,) |

| call_function |

lt |

|

(sum_1, 0) |

| output |

output |

output |

((x, lt),) |

code

def toy_example(a,b):

(x,lt) = call1(a,b)

if lt:

f1(b,x)

else:

f2(b,x)

def f1(b, x):

b = b * -1

return x *b

def f2(b,x):

return x *b

guards:

check_tensor(L[‘a’], Tensor, torch.float32, size=[10], stride=[1]) check_tensor(L[‘b’], Tensor, torch.float32, size=[10], stride=[1])

walk the byte code again for f1

b = b * -1

return x *b

TRACED GRAPH

| placeholder |

l_b_ |

L_b_ |

() |

{} |

| placeholder |

l_x_ |

L_x_ |

() |

{} |

| call_function |

b |

|

(l_b_, -1) |

{} |

| call_function |

mul_1 |

|

(l_x_, b) |

{} |

| utput o |

utput o |

utput ( |

(mul_1,),) { |

} |

other branch

guards: check_tensor(L['b'], torch.float32, size=[10], stride=[1])

check_tensor(L['x'], torch.float32, size=[10], stride=[1])

TRACED GRAPH

| aceholder l_ |

x_ L_ |

x_ () |

{} |

|

| aceholder l_ |

b_ L_ |

b_ () |

{} |

|

| ll_function mu |

l <b |

uilt-in function mul> (l |

x, l_b_) {} |

|

| tput ou |

tput ou |

tput (( |

mul,),) {} |

|

check_tensor(L[‘b’], torch.float32, size=[10], stride=[1]) check_tensor(L[‘x’], torch.float32, size=[10], stride=[1]) # return x *b # mp/ipykernel_1179164/26

linear traces

Dynamo removes all control flow, if/else, loops, exceptions

specializes (bakes in) all non-tensor objects (numbers, strings, classes )

@torch.compile

def fn(f,n):

y = x ** 2

if n >= 0:

return (n +1)* y

else:

return x /y

x = torch.randn(200)

fn(x,2)

def forward(l_x_: torch.Tensor):

y = l_x_ ** 2

mul 3*x

return (mul,)

special cases

Trace integers symbolically

by default it specilizes on every integer in the graph but if a subsequent vall the value changes it traces symbolically but 0 or 1 are always speciaized

multiple traces

import torch

from typing import List

import torch._dynamo

torch._dynamo.config.suppress_errors = True

def my_compiler(gm: torch.fx.GraphModule, example_inputs: List[torch.Tensor]):

print("my compiler() called with fx graph")

gm.graph.print_tabular()

return gm

@torch.compile(backend=my_compiler)

def toy_example(a,b):

x = a / (torch.abs(a)+1)

if b.sum() < 0:

b = b * -1

return x *b

for _ in range(100):

toy_example(torch.randn(10), torch.randn(10))

import torch

from typing import List

import torch._dynamo

torch._dynamo.config.suppress_errors = True

def my_compiler(gm: torch.fx.GraphModule, example_inputs: List[torch.Tensor]):

print("my compiler() called with fx graph")

gm.graph.print_tabular()

return gm

implementation

pep 523, allows python function to see unevaluated frames, function + arguments

normally just calls the function